Museums are at a tipping point. Not a week goes by, it seems, without a headline about how some storied institution is surrendering a fresh batch of centuries-old statues or vases that — oops! — turn out to have been illegally excavated and exported. These high-profile returns beg the question of how they were acquired in the first place.

The answer is that for decades, American museums enjoyed an era of rampant, reckless growth, collecting basically whatever they wanted with virtually no consequences.

For my latest story in The Chronicle of Higher Education (free to read if you register with your email), I wrote about how the problem of looted antiquities looms large at one small museum: Emory University’s Michael C. Carlos Museum in Atlanta, Georgia. It’s a fraction of the size of the Met and the Getty, so its holdings have received very little scrutiny — even though, as I found, many of its objects come from the same questionable sources.

An analysis of the Carlos’s collection paints a portrait of a museum that aggressively expanded with seemingly little regard for what experts say were clear warning signs. At least 218 of the Carlos’s artifacts passed through people who have been convicted or indicted on charges related to antiquities trafficking or falsifying antiquities’ provenance information, according to a Chronicle review of the museum’s online catalog.

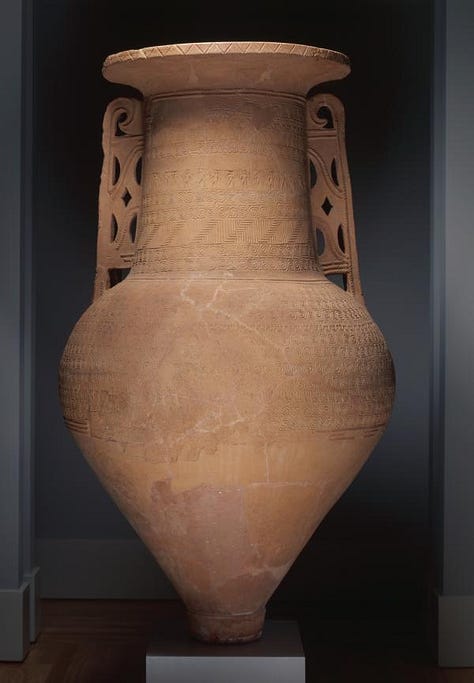

Those items are part of a larger group — totaling at least 562 — whose previous owners and sellers have been linked by authorities to the illicit antiquities trade, have acquired allegedly looted objects, or have had works seized or returned to their source countries. The items are predominantly in the museum’s roughly 1,160-piece Greek and Roman collection.

Notably, the Carlos accepted dozens of relics after their past handlers had been raided by authorities or accused of criminal activity, records indicate. In an interview, the current director, Henry S. Kim, did not dispute The Chronicle’s findings and agreed that there were “red flags” in some objects’ histories. He also said that the museum did not know the provenances of a number of antiquities when it acquired them.

Most of these acquisitions stemmed from a directive handed down by the man for whom the museum is named: Michael C. Carlos, an Atlanta businessman with a passion for Greek art. In 1999, he announced that he was giving the museum $10 million to beef up that part of its collection, and the museum hired a new curator to get the job done. That curator had worked for a now-notorious New York art dealer, one who went on to stand on trial for allegedly masterminding a global antiquities-trafficking network.

Once in Atlanta, the curator acquired dozens of relics from his old employer, as well as from plenty of his infamous associates. These beautiful things helped put the museum on the map, boost Emory’s reputation, and bring crowds and money to campus. Ostensibly, universities are tasked with training future scholars to study and care for artifacts. But experts fear that the Carlos’ practice of asking few questions may have incentivized the theft of those very works.

“My instructions,” the Greek and Roman art curator once said, “are to look for not the best, but the very best.”

And now the museum has to reckon with that legacy.